I started riding the bus in Boston in my second year at Harvard – in the first year, I was too afraid of making a fool of myself to do it. I knew that I’d have to pay for it somehow, and I imagined myself holding up an entire bus of commuters as I tried desperately to shove soggy dollar bills into a slot.1 My change of heart about the bus came after I spent three months in India in the summer of 2015. Hailing autos and trying to explain where I needed to go without speaking any Hindi made the MBTA incredibly tame by comparison.

In any case: I started riding the bus in my second year, but my route is a popular one between 7:30 and 9:00 am. During the winter, when there’s too much snow to ride a bike without some Masshole yelling at you (a story for another post), the bus looks pretty appealing.

So, sometimes you’ll be standing, waiting for it, shivering, and it’ll be so full that it passes right by you.

You have one way that you can guarantee that you get on the bus: you can walk four or five blocks down to an earlier stop. I’ve done this a few times, but every time I have I’ve felt deeply ashamed if the bus does end up skipping the stop closest to where I live.

Here’s my thinking about why it isn’t right to walk to an earlier stop:

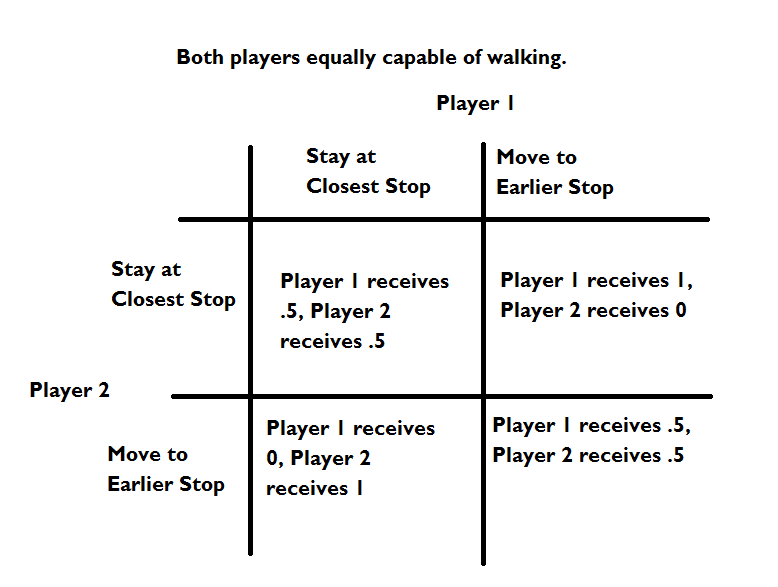

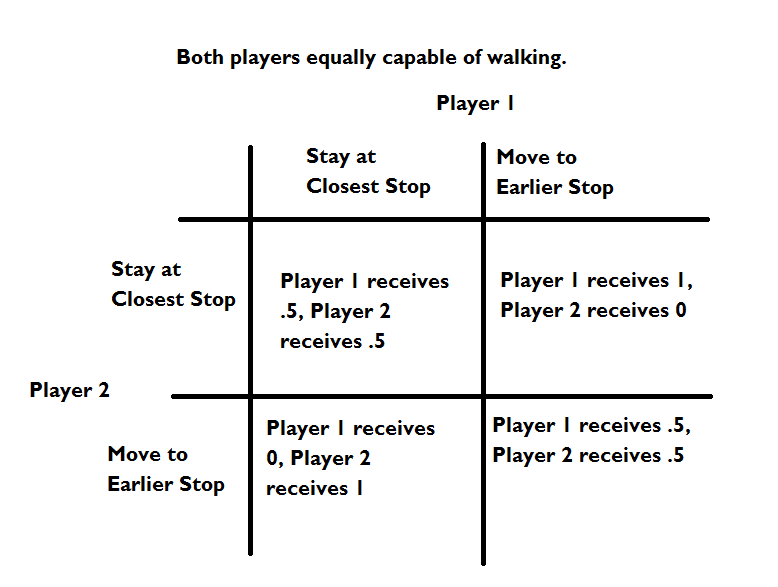

Suppose there are just two people, and they’re getting on the back of a motorcycle, rather than a bus. Only one can sit on the motorcycle, so if they’re at the same stop, they’ll flip a coin to determine who gets to take that transportation. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say that each player receives utility 1 if they make it to work on time, and 0 if not. Then, the game they face looks like this:

As this is, I don’t see anything inherently wrong with walking to an earlier stop – if we both do it, we end up just flipping the coin the same as we would before. The only thing that’s really wrong about this is that we only benefit by taking advantage of the other player’s naivety, but they could easily join us at the earlier bus stop if they thought of it.

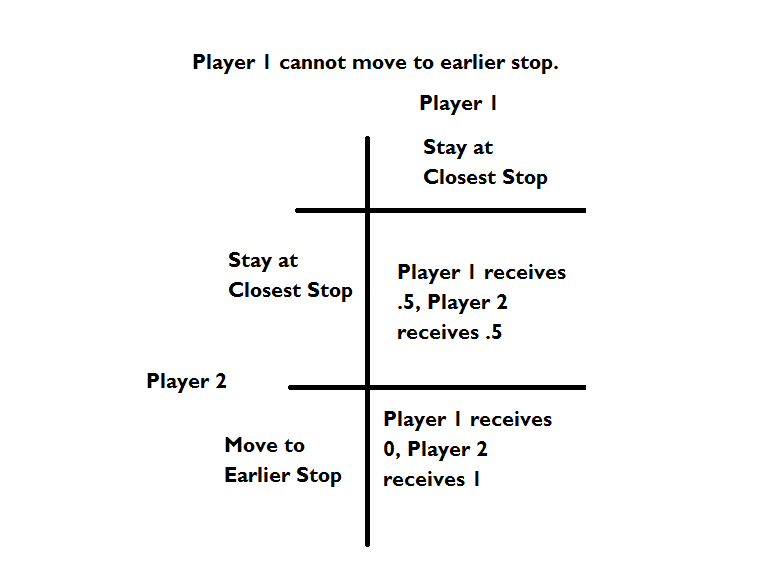

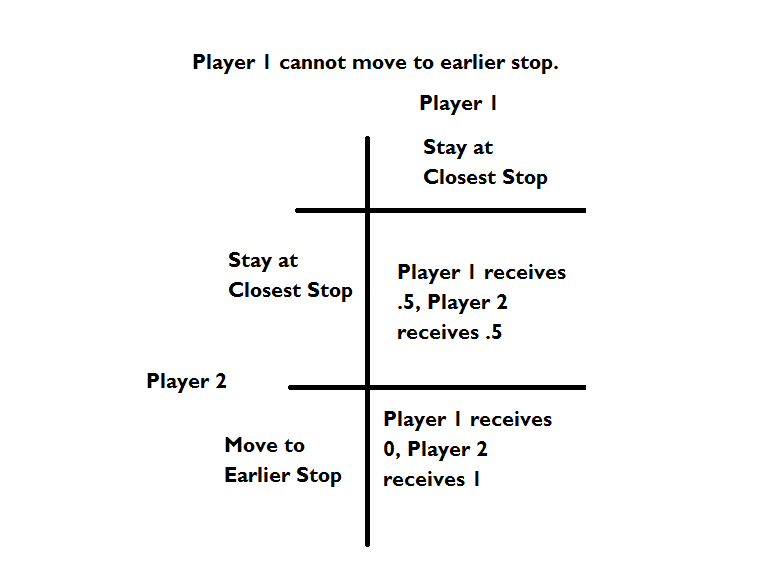

However, if they can’t walk that far – if they have a disability or if they’ve got kids in tow (suppose you can stick the kids on the motorcycle) or if they’ve just got a ton of bags, the set of choices looks like this:

Now I think it’s clear that you’re not justified in moving the earlier stop, since your movement makes them late with certainty. This probably happens pretty often in real life; it isn’t unrealistic to think that some proportion of people taking the bus would find it painful or impossible to travel another few blocks. Since we can’t know whether our companions at the bus stop are in this situation, maybe we should not move to the earlier stop just in case.

Now I think it’s clear that you’re not justified in moving the earlier stop, since your movement makes them late with certainty. This probably happens pretty often in real life; it isn’t unrealistic to think that some proportion of people taking the bus would find it painful or impossible to travel another few blocks. Since we can’t know whether our companions at the bus stop are in this situation, maybe we should not move to the earlier stop just in case.

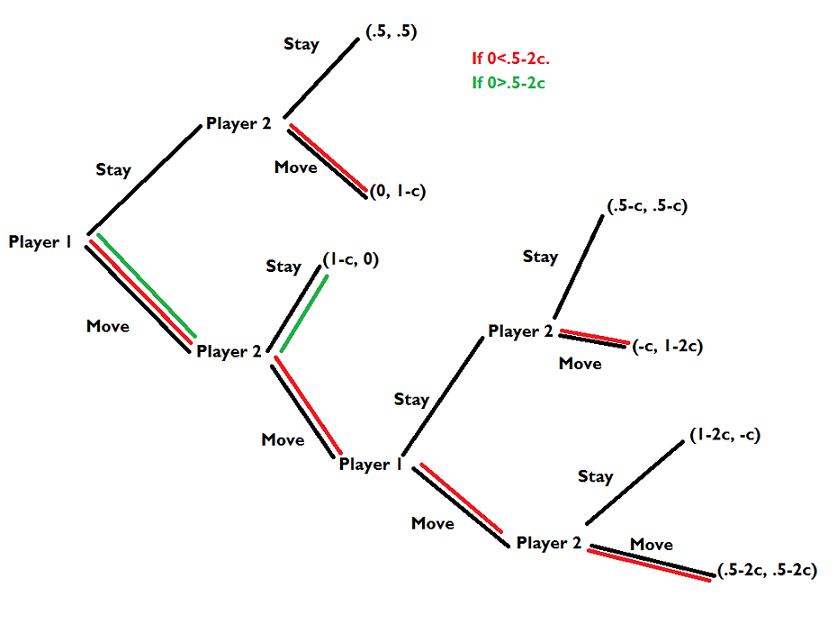

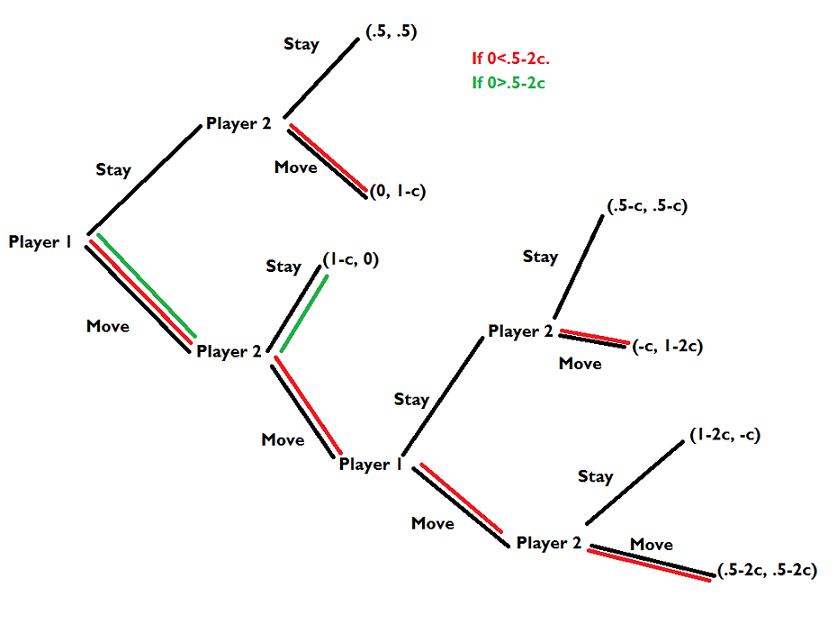

There’s a third issue. Consider now a game with 3 stops, where traveling an additional stop costs c. Player 1 chooses first whether to move or stay, and then player 2 chooses. Assume that 1-c>.5, so that it is worth it to move if the other player stays. Then, 1-2c>.5-c. It must also be that .5-2c>-c, since we could add .5 to both sides of that inequality and get back to our previous conclusion that 1-2c>.5-c.

The green path indicates what happens if 0>.5-c: player 1 moves and gets on the bus, and player 2 doesn’t move and doesn’t get on the bus. However, the interesting outcome is the red path – in this equilibrium, both players move until they run out of bus stops, and then they both flip the coin to decide who gets to ride on the bus. [Look up “backward induction” and “dynamic games” if you’re not sure how I came to this conclusion.]

What’s interesting about this? Well, at the end of our dynamic game, for some values of c, both players are left worse off than they would’ve been if they could’ve just cooperated. It’s the prisoners’ dilemma.

Kant’s categorical imperative goes: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” I may be misunderstanding this, but it sounds like “choose no action which would make everyone worse off if everyone chose it.” So, stay at the first bus stop. (This site seems to agree with my interpretation, but this article doesn’t.)

Let’s suppose for a second that Kant says we should cooperate in “Prisoners’ Dilemma” style situations. Public goods provision is one such situation that crops up over and over – why should I pay for a road if I know you’ll pay for a road? If we all think this way, no road will be built without government intervention. However, if we all followed the categorical imperative, we wouldn’t need government public goods provision. I wonder whether Kant concludes that there is little need for government in an ideal world?

1. In the two years I’ve been riding the bus now, this scenario has happened at least five times to me. It is just as mortifying as I imagined it would be, but what I didn’t know is that if you struggle long enough, the driver will either seize your money and feed it to the bus themselves, or they’ll tell you to sit down. This to say: any suffering on the bus is temporary. Back

Now I think it’s clear that you’re not justified in moving the earlier stop, since your movement makes them late with certainty. This probably happens pretty often in real life; it isn’t unrealistic to think that some proportion of people taking the bus would find it painful or impossible to travel another few blocks. Since we can’t know whether our companions at the bus stop are in this situation, maybe we should not move to the earlier stop just in case.

Now I think it’s clear that you’re not justified in moving the earlier stop, since your movement makes them late with certainty. This probably happens pretty often in real life; it isn’t unrealistic to think that some proportion of people taking the bus would find it painful or impossible to travel another few blocks. Since we can’t know whether our companions at the bus stop are in this situation, maybe we should not move to the earlier stop just in case.